A while back I wrote a blog post about anxiety in childhood and teens from a webinar I took through the Institute of Child Psychology (see blog here). Every so often, they offer a free one hour webinar about various topics, and a few weeks ago I was able to take the webinar on understanding childhood trauma.

As a trauma informed pediatric occupational therapist, who has plenty of experience working with children who have had hard experiences and display what the average person would identify as “aggressive behaviours”, I am very interested in this topic. I believe very strongly that a lot of behaviours that come off as inappropriate or aggressive in children often stem from being overwhelmed by their situations and reacting to a sense of fear or danger. Most of the time, people do not approach these behaviours with the thought that children may be acting out because of something that happened TO them and not because they are choosing to misbehave. So let’s dive into a discussion about this through the webinar I took. (Note, this is a longer blog than I usually write so buckle in or save it to return to later)

This webinar was delivered by Tammy Schamuhn, a psychologist, instructor and consultant and co-founder of the Institute of Childhood Psychology. She begins the session defining Trauma. It is important to note that if someone experiences trauma as a child, it can stay with them through the rest of their lives – so if any of this resonates with you or someone you know as an adult, it makes sense because experiences don’t just go away as you grow.

What is Trauma?

- Trauma is an experience that may be perceived and traumatic for one individual… this means that something that may not seem traumatic to you, may be extremely traumatic for someone else

- “Small T” traumas

- are events that exceed our capacity to cope and can cause a disruption in emotional functioning. These aren’t necessarily life or body threatening, but can leave the individual feeling hopeless (ex: divorce, infidelity, abrupt relocation, financial difficulty…. in kids perhaps reoccuring bullying, parental divorce, living with a parent with untreated mental health disorders etc) These traumas tend to be overlooked by the individual who has experienced the difficulty because they may seen common, which leads us to shame ourselves for any reaction because we are “over-reacting”. Sometimes, the individual doesn’t recognize how these events may have effected them, and often can be overlooked or dismissed by a therapist.

- “Large T” trauma

- is an extraordinary and significant even that leaves an individual feeling powerless and having little control in their environment. This could be something like a car accident, sexual assault, natural disaster etc. These traumas are more likely to be identified as trauma by the experiencer, and often avoidance is a huge part of coping with these traumas. One large T trauma is often enough to cause severe distress and affect an individual’s daily life.

- trauma often overwhelms our capacity to control how we respond to the environment as we can disconnect from ourselves and our reality as our brain tries to keep us safe

- Something that is important to note about trauma is that someone who has experienced trauma may be in a safe situation in the present, but their brain may be overwhelmed about the past, which can trigger stress responses even though they are physically safe in the present

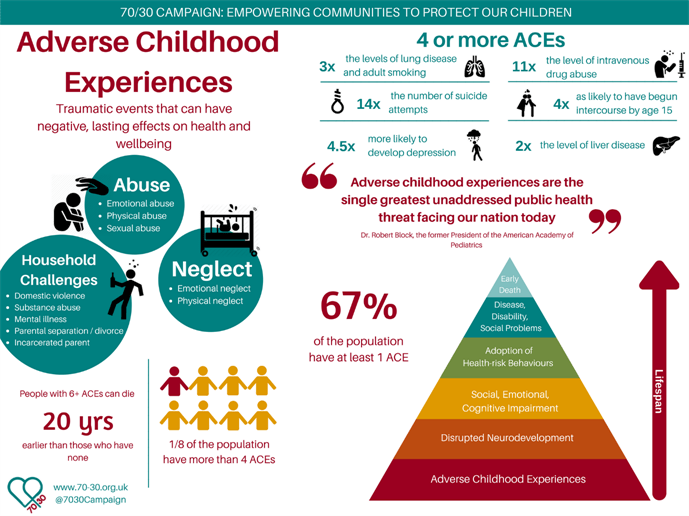

Looking at trauma specifically in Children can be confusing because children SHOULDN’T be experiencing trauma. Remembering the small T traumas as well as the large T traumas, we’ll change our terminology to something that has been studied quite a bit in the last 30 years: Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs). ACEs are traumatic experiences experienced in childhood that can cause trauma. Studies are being done that show that these can change the way our brain is wired due to the high doses of stress, and can affect immune system, hormonal system etc.

Some examples of ACEs might include:

- neglect

- physical, emotional, sexual abuse

- witnessing violence

- car accidents

- physical injury

- major medical procedures

- loss of parent/caregiver

- loss or threat of loss of relationship

- intergenerational trauma

- high conflict divorce

- etc…….

To get a bit more information on ACEs, I’ve embedded some videos below (Dr Burke, in the last youtube video linked, is one of my favourite Ted Talks, and is one of the reasons I am so interested in a trauma informed lens for all my clients including children and teens)

Child’s Brain Development

I won’t go too deep into the development of the brain because that can be a complex thing to understand, but it is important to understand the different parts of the brain, what they do and how they can be affected by trauma. By understanding a bit more about the brain, you can understand why certain behaviours might happen, and how you can support a child in this time. (if you would like, you can scroll through this to get to some of the strategies presented in this course)

The first part of the brain that develops is the Brainstem (1st brain). This is the area for basic survival instincts as well as the sensory motor area of the brain. This part of the brain is almost always intact unless there is neonatal trauma involved – ex: malnutrition of mom, genetic disorders etc.

The second part of the brain that develops is the Limbic Brain (2nd brain). This is the space for processing emotions and memory, which in extension is where emotional development and the creation of attachment happens. In a healthy environment without trauma, this area of the brain is often developed by 7 or 8 years old.

The final part of the brain that develops is the Cortical brain (3rd brain). This is where we see learning, thinking, problem solving, planning, rational thoughts, inhibition and language being developed. When a child has experienced much trauma, this part of their brain may be compromised.

Amygdala – The amygdala is the watch dog of the brain – it’s the part that surveys the scene to make sure you’re safe if there is a felt threat to your environment. The amygdala is also the part of the brain that sounds the alarm and triggers the fight, flight freeze and collapse reactions:

- Fight – attack, aggressive behaviour, etc

- Flight – running away from a situation

- Freeze – staying still, unable to move

- Collapse – often in trauma people will dissociate; their body goes into shock and checks you out of the situation so you don’t experience the pain of the moment

With the amygdala, if it is activated a lot, it can become bigger and might be set off more easily. This means that it might not take a big event to set the amygdala into action (aka the child might be triggered into survival mode more easily). When the amygala responds, your logical part of your brain brain disengages, which means as parents, we must remember that we might not be able to use logic and talking to soothe our children in this time.

Hypo aroused vs Hyper aroused

When we talk about the stress responses above, we can categorize fight/flight as the hyper aroused reactions, and freeze/collapse as the hypo aroused reactions. Depending on your history and how your behaviours helped you survive your trauma, you will cycle through both hyper and hypo aroused responses. Often times, however, the HYPO aroused response is missed in children because they are quiet, shut down, or don’t display emotions, and therefore are not a problem to anyone around them. Children who respond with HYPER arousal, are often reported as having “behaviours”, being aggressive, or avoidant. In opposition to this, if a child is reacting to something with silence and stillness, they might not cause disruption in a classroom for example, and therefore their behaviour might go unnoticed.

Left vs Right brain

The brain is split into the left and right brain when it comes to information processing. The right side of your brain is about emotions, feelings and creativity, while the left side of your brain is logical, organized and detail oriented. Both of these sides are connected by the corpus collosum, which allows them to share information.

When a child experiences trauma, the right side is often underdeveloped, and the two hemispheres won’t communicate properly. When this happens, you might see someone be removed from their emotions and memories OR you might see someone who is very reactive and chaotic – the lack of communication between left and right brain can cause a lack of balance.

Supporting a child using a Trauma informed lens

Before we dive into this section, it is important to recognize that you might not know if a child has experienced trauma or what those traumas might be when you work with a child, even if they are your own child. Often times, childhood trauma can be confused with presentations of ADHD, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Depression, Conduct Disorder, and Oppositional Defiant Disorder. Because I am not a health professional that diagnoses children and only works with them to help them succeed in their daily occupations (see my what is Occupational therapy blogs here, here and here), I like to approach every child with this trauma informed lens to help create a safe space, and a trusting relationship with them.**

If you are not familiar with the diagram to the right, this is Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Essentially, he speaks about how we start from the bottom of the triangle, and once those needs at the bottom are met, we can work on satisfying the needs above. As someone working with children, whether as a parent, caregiver, educator or healthcare provider, it is important to recognize that children too follow this structure of needs. This means that if a child is not feeling secure in their physiological needs and relationships with family, they may have trouble succeeding in school and forming friendships. Ensuring that they feel safe is the first step to helping a child succeed.

In a child’s environment, it is important to try to create predictability and rhythm to help them feel safe. This doesn’t only mean giving them a safe space to sleep, play, learn and eat, but also means building routines. Routines/schedules can help children feel safe as they know what to expect throughout their day – for example, if they wake up knowing when their meals will be, when they go to school, what time is bedtime etc, they will be more confident approaching each task. Sometimes this might mean creating a visual schedule for them that they can look at if they are feeling anxious, and perhaps making a school specific one for them to carry around at school.

In a safe space, when they feel triggered, we can then work with them through regulating their trauma responses, validating and comforting them and then guiding them through their coping skills. Remember, you need to practice coping skills with them when they are feeling calm and focused so they know what to do, but in a trauma response they still might need your guidance to initiate and move through them.

Attachment focused intervention

Considering that children need to form solid attachments to feel safe in their environment, we can also use this idea in understanding that children need to heal in their relationships before starting healing in other forms.

Interventions focused on attachment are important because kids need to know that they are able to explore their world, and fail, and know that their support system will still be there afterwards.

Attachment is important as it acts as a protective factor and impacts how we perceive the actions of others. Through a healthy attachment/relationship, children develop their capacity to identify and manage emotional states, and increase their capacity to explore the world. Through attachment, we experience safety, and we also learn how to make relationships with other people in the world. Throughout this COVID time, we have heard people say constantly “children are resilient” … which they absolutely are, but we have to remember that they shouldn’t be left to be resilient on their own. Learning how to cope with hard things, to connect with others and to manage their emotions are things that should be modelled by the adults in their life. This is our role.

As an adult, we need to be aware of a child’s cues – learning to read non verbal cues and behaviours, and teaching others what they signify can help us support our children’s emotions. Being able to recognize when a child is going through a hard time without depending on them vocalizing it, can help us empathize with and validate their feelings, and then help initiate their coping strategies.

Here are a couple strategies you can teach your child (when they are calm) and help them use when they are in a difficult emotional state:

Calm the brain stem – grounding exercise

Counting down from 5, this helps children come back to the present

5 – Look around for 5 things you can see and say them out loud

4 – Pay attention to your body and think of 4 things you can feel and say them out loud (ex: I feel my feet warm in my socks, I feel the pillow I am sitting on)

3 – Listen for 3 sounds and say them out loud

2 – Say two things you can smell – if you’re allowed to, it’s okay to move to another spot and sniff something. If you can’t smell anything, say your favourite smells

1 – Say one thing you can taste, if you can’t taste anything say your favourite thing to eat

Take a deep belly breath to end

Distraction

This is a simple one – sometimes, just like with adults, children’s emotions are too big for them to process and it is hard to calm down. In these situations, distraction can be a strategy to try. Something as simple as playing I spy with my little eye, and pointing out items in the child’s surrounding can be helpful to bring them out of their emotions and into the present. If the surrounding environment isn’t filled with I Spy worthy items, there are loads of photos you can use on your phone instead!

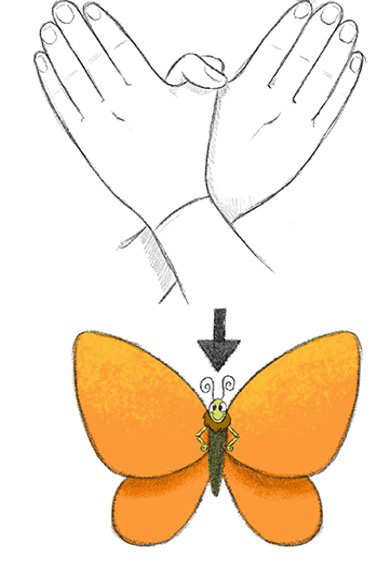

Butterfly tapping

Borrowed from EMDR therapy, is the butterfly techique. When children are experiencing a traumatic moment, have them cross their hands like the diagram to the left, to look like a butterfly. Help your child imagine a place that makes them feel very safe and calm (maybe this is something you can practice in a calm moment when they are not panicked). Have your child put the butterfly hands over their chest and do gentle tapping on their shoulders while they tell you what they see, smell, hear etc in their safe place. If they want they can come up with a name for this safe space that helps them remember it more.

Manage Big Feelings

It is important to connect with your child and validate their emotions when they are experiencing a challenging time. Acknowledging your child’s feelings using words, body language and tone can help them connect with you, and then make it easier to engage with the challenge they are experiencing. Remember, their logical brain is probably not working, so don’t use too many words, use simple language and make sure you are staying calm. They might have a meltdown, but staying with them and showing them you are a reliable person to be with when big emotions are happening is important.

You can use the CAT model as a guide

- C – Communicate limit – ex: “people are not for hitting”

- A – Acknowledge feelings – ex: “you are feeling upset because he took your toy”

- T – Target an alternative – ex: “let’s go find you another toy”

**** remember, sometimes it’s as easy as redirecting to another toy or activity, sometimes children will need you to help them with redirection, such as going with them to a quieter space, reading a book, breathing etc.

Aggression as a response

It’s important to remember that sometimes children will respond to emotions with aggression. When a child gets aggressive, this is often the fight response happening and they are unable to reason with themselves to calm down. They are reacting to past emotions/feelings and are feeling unsafe in this moment (ex: experiencing a flashback).

When a child gets aggressive, remember they are in a threat response so they might not be able to hear you. Don’t personalize their words and actions, it is not directed towards you. Keep yourself safe and keep your child safe, move to a safe space if needed. If you feel safe providing them with a coping skill, do so, otherwise let them calm down a bit. Make sure to recognize that they are human, they are experiencing something difficult, do not punish them for their aggression but help them work through it and try to talk about what happened afterwards.

Consider “What happened to you” instead of “What’s wrong with you”

Jen Alexander

At the end of the day we need to remember and recognize children’s humanness. Just as adults can experience trauma and big emotions, children can too. Try to move from judgement of children’s behaviours to compassion for what they might be feeling.

Whether you are a parent, health care provider or teacher, I believe it is important to approach all children using a trauma informed lens to understand where their behaviours might be coming from and how you can support them. The Institute of Child Psychology often offers these free one hour webinars, and has a huge variety of self paced courses you can purchase to learn more. I will be continuing to engage in their content and to share it as I can here on this platform.

(This is not a sponsored post, I am just very passionate about education and helping others get informed, especially when there are ways to do it from professionals in a cost effective and accessible way)

Please feel free to message me with any questions about this content, the webinar or anything else – my contact info is here

This goes into a lot of depth! I think children are labeled as “naughty” too often when really they might be struggling. Sometimes they need compassion and empathy, not punishment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh my goodness I completely agree!! I have worked with so many kids who have been seen as “aggressive” or “badly behaved” and then when you hear the stories of their past it is so clear how hard they’ve had it! They just need to be given some compassion and love and a strong attachment with an adult

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, kids need to feel safe and loved. A sense of security can go such a long way. I had a pretty good childhood and I wish all kids got that opportunity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This is an excellent post. A lot of concrete ways to work with a child that has experienced trauma.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I appreciate this comment so much! Any additional ideas are always welcome!

LikeLiked by 2 people

“This is the most important job we have to do as humans and as citizens … If we offer classes in auto mechanics and civics, why not parenting? A lot of what happens to children that’s bad derives from ignorance … Parents go by folklore, or by what they’ve heard, or by their instincts, all of which can be very wrong.”

—Dr. Alvin F. Poussaint, Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

__________

Basic child development science/rearing should be learned long before the average person has their first child.

By not teaching this to high school students, is it not as though societally we’re implying that anyone can comfortably enough go forth with unconditionally bearing children with whatever minute amount, if any at all, of such vital knowledge they happen to have acquired over time?

I know I didn’t know until I researched this topic for the specifics.

If we’re to proactively avoid the eventual dreadingly invasive conventional reactive means of intervention due to dysfunctional familial situations as a result of flawed rearing—that of the government forced removal of children from the latter environment—we then should be willing to try an unconventional means of proactively preventing future dysfunctional family situations: Teach our young people the science of how a child’s mind develops and therefor its susceptibilities to flawed parenting.

Many people, including child development academics, would say that we owe our future generations of children this much, especially considering the very troubled world into which they never asked to enter.

__________

“It has been said that if child abuse and neglect were to disappear today, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual would shrink to the size of a pamphlet in two generations, and the prisons would empty. Or, as Bernie Siegel, MD, puts it, quite simply, after half a century of practicing medicine, ‘I have become convinced that our number-one public health problem is our childhood’.” (Childhood Disrupted, pg.228).

____

[Frank Sterle Jr.]

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this! I have learned so much in the past year as an occupational therapist and the past couple years as a supply daycare teacher that I think everyone should be able to have access to as new parents! I’m trying my best to share all I can on this blog, but I have so many things I haven’t been able to put into writing yet.

LikeLike